The women fish farmers I have met on this journey are from two different districts: Chitwan and Nawalparasi. The two are not that far from each other. Or, they are. It depends. “Depends on what?”, you may ask. Well, Bharatpur in Chitwan is about a 160 km journey from Kathmandu, about a 5 to 6-hour drive. Driving from Bharatpur to Lumbini in Nawalparasi will take about 2 to 3 hours. My first time going to Nawalparasi, I was struck by the road, or rather, its lack thereof. We drove along a riverbed. In the monsoon season, there is no way to go through. Sometimes they travel by scooter and sometimes they travel by tractor. That is some perspective for those of us in Finland who travel between cities in comfortable trains and buses, often complaining about the Wi-Fi connection.

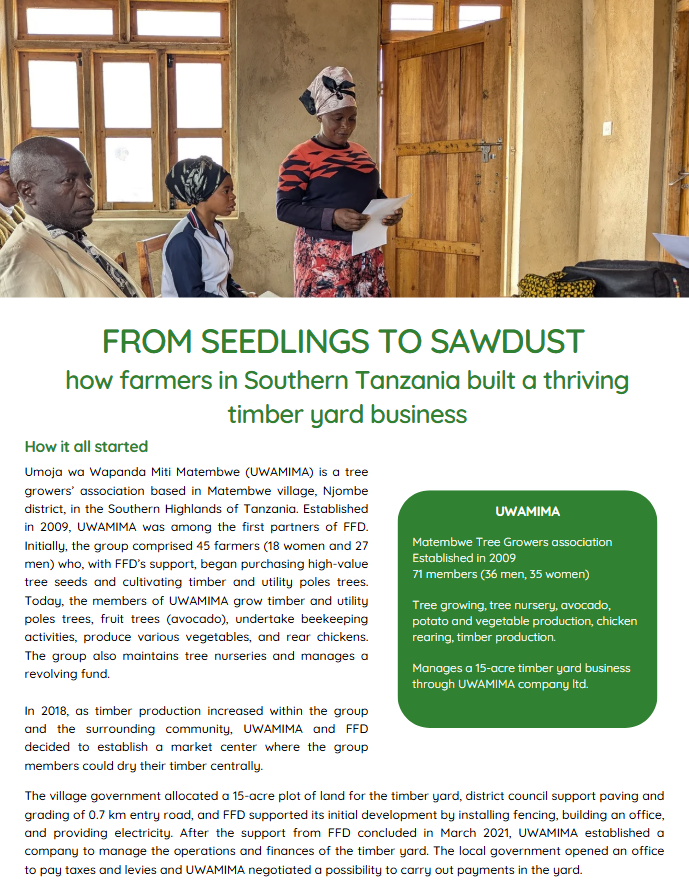

In these two regions, the women fish farmers are as diverse as they come. Some are Hindu, some are Buddhist, some are Tharu, some are Bhramin and their ages vary from late teens to the 90s. They all are so different, but there is one thing they all have in common- fish and fish farming. They all grow fish in small or big ponds, depending on their own circumstances. They all cook fish and serve it to their families and share it with their neighbours and sell it too. For this was how the story started. With small ponds to provide for their own families in 2013, and now in 2023, they are establishing cooperative-based enterprises through which they can sell their increased production and gain a higher income.

They have come far these women from the Nepal Terai, learning the basics of fish farming, interacting with each other, sharing the responsibilities ranging from feeding of fish to harvesting of fish. Even though many of them admit they do not like harvesting fish. It is tough work, and the ponds can be deep and scary. They would rather the men do the harvesting as well as the digging and preparation of the ponds for stocking. Fish farming is undoubtably scary for the women sometimes. They may encounter wildlife like rhinos and wild boar, or even the odd crocodile. Having men around at times like this is always important. They can help provide protection.

Although the fish farming activities we have supported over the years have been labelled women fish farming, I like to think of this more pragmatically. Whole families have been involved. The gender equality aspect that we have sought to support cannot be achieved by just supporting women alone. Rather, the men in the families and in the communities must also be involved. By being inclusive rather than restrictive, we have been able to pave the way for increased women participation in fish farming.

In this 10-year journey, there are also those moments when hardship has been faced. Nepal is a natural-disaster prone country, that carries a huge burden from climate change. It is a landlocked country between two dragons, China and India, that sometimes use their power positions ruthlessly to favour their own agendas, including barring of fuel and food transportation across the borders. Developing self-sufficiency and resilience building is Nepal’s only way out of these crises. In the meantime, Nepal and her people continue to suffer turmoil in the face of natural calamities.

The Gorka earthquake in 2015 stopped our operations and damaged some fish farms and homes. The fear in the eyes of the women around me is something I can never erase from memory. The wonder of “why is the earth is shaking and causing havoc?” and questions of “will we survive?” surrounded us. Their collective fear for their families and themselves but also simultaneous concern for my wellbeing was astounding. FFD and the donors ended up supporting reconstruction measures with part of the project funding. The joy and appreciation of the families that benefitted from that support was unsurmountable. I will not forget the family that showed off their brand-new pink house to us, with tears in their eyes. They had lived for almost a year in their chicken coop.

The lessons I have learnt from these brave women fish farmers in Nepal are extremely valuable. Girls, women, wives and mothers everywhere around the world, face the same struggles in the lives, no matter their language, social, economic, cultural or religious background. Their endurance in the face of hardship is mind blowing. How much they have transformed their lives is amazing. With the earnings they have got from fish farming, they have managed to improve their livelihoods, better their family nutrition and pay for the education of their daughters (and sons). I have seen women, young and old, learn to read, learn to use a computer, create a selling campaign and even create a monitoring system. We have sat together and mused about how their groups and cooperatives run, about how to encourage children to eat fish and so forth. We worked with their community schools and put together school meals from fish and cleaned the surrounding environment together.

My being a twin to these women has never been about 'teaching' anyone but being someone to lean on, being a supporter, a sister, a daughter.. maybe a granddaughter...who walks the journey with them, and has them walk with me. So for a decade gone, I thank the women fish farmers of Nepal, and hopefully we shall continue to walk together for a decade more.

Roseanna Avento

Kobe Global

Twinning Partner Representative Finnish Fish Farmers’ Association

The project: ‘Women for Entrepreneurship and Resilience - transforming fish-farming and forest value-chains’ project in Nepal’ is funded by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland from 2021-2024